|

i. porky’s 3: the quickening

I

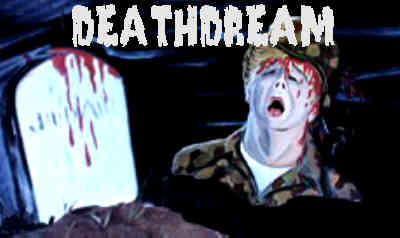

was watching Bob Clark’s drive-in masterpiece Deathdream

(1972) with some friends and I noticed they were cringing

because the actors weren’t, um, exhibiting the subtleties

of their craft, shall we say. I tried to insert other stars

into the film like reverse paper dolls -- replacing the

faces and bodies under the outfits. And pretty soon I had

Jessica Lange, Dustin Hoffman and Chloe Sevigny acting out

Clark’s Vietnam-era Freudian nightmare.

Here’s the back story before I

bring our fine, academy-approved thespians into these low

budget environs. Bob Clark (much later of Porky’s fame)

and Alan Ormsby (later screenwriter for 1982’s Cat People

and Karate Kid III) concocted the most delirious

and unjustly ignored horror films of the early/mid-70s:

Deranged (1974), Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead

Things (1972), Deathdream and Black Christmas

(1974). Deathdream is about a young man’s homecoming

from Vietnam and the potential hideousness of a mother’s

love. It’s better than The Deer Hunter and Coming

Home where Vietnam is concerned and much better than

Robert Redford’s Ordinary People Mom-wise, but it’s

also a horror movie so nobody gives a shit.

We first see the soldier’s family

sitting around the supper table. The perfect little family

but something’s off. The mother has her head tilted like

a little bird, her face a mask of Valium calm as she rambles

on about her son, Andy, and how nobody on her daily route

of wifery can wait for him to come home. She just chirps

and chirps and the father and the daughter barely contain

a series of twitches and tics that tell us all is not right

with their little carpenter’s gothic world.

The doorbell rings and the

first of many haunted shots bathed in front porch light

ensues. A local ROTC officer brings the family word that

their son, Andy, died in combat. Of course, this completely

shatters the scene and some kind of animal order takes hold

in the house, something much older than 1972. The mother

makes some  kind

of pact with the dark woman/mother forces by candle light

and that very night Andy returns home. kind

of pact with the dark woman/mother forces by candle light

and that very night Andy returns home.

The family immediately begins whitewashing their hopeful

expectations all over him while he remains quiet, unblinking,

unfamiliar with his own body. This is glorious, they tell

him. He can resume his sunny youth. There’s dating to be

done. Wait until the neighborhood sees how great he looks

in his uniform. Andy, can you believe, they ask him, can

you believe they said you were dead?

I was, Andy answers. Dad looks

at Andy like his boy’s a busted appliance. Daughter looks

at Mom like she’s a story problem. Mom looks like she’s

trying out for a 60s Anacin commercial. Andy looks at Mom

like they’re in cahoots. Then Andy’s face cracks open to

reveal… what? Like baby teeth, teeth with just a little

too much space between each one, gums that are too pink,

and what’s that sound he’s making? Well, it’s a laugh I

guess, but it seems to come from a ventriloquist hidden

off screen. The laugh doesn’t stir his body, which remains

perfectly immobile, one hand caught like a spider in the

lace tablecloth, the other limp in his lap. Still, the family

takes what it can get and soon they’re all laughing with

high-strung warmth.

Of course, Andy’s dead. It’s the

old Monkey’s Paw story retold with counter culture

vigor. By the autumnal, muted colors of the porch light,

the family unravels slowly. Andy just sits in his old room

in the dark, rocking back and forth in a chair. He’s surrounded

by boyhood clarity (a Scooby Doo light switch, some cowboy

toys) but he’s just more bric-a-brac now. To the family

anxiously awaiting a return to normalcy below him, the rocking

begins to sound like a tell-tale heart.

In a day or two, they draw Andy

(Richard Backus, who’s sad and terrifying and apparently

never acted again) into the backyard for a picnic where

all the young kids from the neighborhood descend upon him

to quiz him on his heroism. In a fine exhibition of what

military service has made of him, he strangles the family

dog before their eyes.

This sends Dad to the local bar

and then back home where he hopes to confront Andy. No Andy,

just an empty rocking chair. Dad stumbles down the stairs

to see where his pet-strangling war hero son’s gone:

Daughter: (Hearing her father slamming around in

Andy’s room) Daddy? Daddy?

Father: (Seeing a car

pull out of the driveway) Is that Andy?

Daughter: Yes, Daddy. He

went out the back door. Mother gave him the keys.

Father: (Calling out

to his wife) Christine! Christine!

(Mom appears)

You let him go!!??

Mother: Why not? I’d leave

too if my father came home drunk.

Daughter: Daddy? What’s

the matter?

Father: (Shoving her

aside) Oh, mind your own goddamn business!

John Marley, the film producer who wakes up to find his

prize race horse’s head among the folds of his satin sheets

in The Godfather, plays Dad as a befuddled sleep

walker through the middle class until his only son returns

from Vietnam a blood drinking ghoul. Lynn Carlin,

who plays the Mom, is perfect. Underneath a gauze of pain

pills, muscle relaxants and tranquilizers there’s this coyote

mother who must protect her little pup at all costs. And

little sister is just a teeny-bop cipher, humming along

on an oblivious teenage track that just took a detour to

some dark cave where coyote mothers and ineffectual, drunken

fathers hunch down in darkness until this unexpected flurry

of evil spirits passes by. Sis is an accessory and one Mom

is willing to jettison to protect her darling walking corpse.

The acting by all three leads is so emotionally jagged and

just plain off that the movie never lets you settle in to

its rhythms. We are never offered melodrama as a substitute

for discomfort.

It’s a crazed scene of family dysfunction

and when you insert Lange, Hoffman and Sevigny (or any other

Hollywood A-list threesome), it simply doesn’t work. Why?

Because perfect horror acting is pitched at either hysteria

or catatonia. Pitch a performance somewhere in between,

the realm where most Hollywood actors find Oscars and critical

acclaim, and the whole scene collapses. Most mainstream

Hollywood acting is about rhythms, keeping things on the

beat is essential. Occasionally a scene will change up the

timpani beats for rimshots, but rarely does a whole movie

work off-the-beat. It simply isn’t done. Except in horror

films or, for that matter, exploitation films in general.

Here the rhythms are always off and to great effect. Even

teen slasher films which give you a cadence as predictable

as a Casio drum sample, usually (the Scream series

being an exception and a horror novelty at best) benefit

from strange performances: Crispin Glover in Friday

the 13th – The Final Chapter (Joseph Zito, 1984),

John Saxon and Ronne Blakely in Nightmare on Elm Street

(Wes Craven, 1984), etc. Though the technical rhythms

(editing, lighting, music) of these genre exercises are

etched in stone and delivered with stone age pragmatism,

performances like these keep us from engaging completely.

Only in genre exercises is this essential. In a mainstream

Hollywood product, the audience has to be engaged, often

before the opening credits are through. In horror and exploitation,

it’s either the blank or the dervish. In between is inconsequential.

"Bad" acting enhances delirium, feverishness and horror’s

powerful arrhythmia.

ii. waldorf

salad and other just desserts

In the

last twenty years Hollywood has been trying to weld B-movie

thrills onto A-movie sheen and it rarely works. I suppose

it all started with Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Here

we have a pulp novel by Ira Levin, produced by the king

of B-movie thrills, William Castle, and directed by Eurostentialist

Roman Polanski. Mia Farrow and John  Cassavetes

share lead billing and, to their credit, their method chops

pretty much lead them just shy of catatonic. In fact, most

of the cast, good, evil and otherwise, play the script jaded,

like they’re saying, "so it’s the devil in the Big Apple,

what else ya got?" It’s a fine ruse and it keeps the stars

from "peeling away layers" and "finding motivations".

Even the final Satanic coffee clatch is played like brunch

at the Waldorf: "Hail, Satan," they lift their goblets and

chant with all the conviction of conventioners toasting

sprockets and sales figures. Cassavetes

share lead billing and, to their credit, their method chops

pretty much lead them just shy of catatonic. In fact, most

of the cast, good, evil and otherwise, play the script jaded,

like they’re saying, "so it’s the devil in the Big Apple,

what else ya got?" It’s a fine ruse and it keeps the stars

from "peeling away layers" and "finding motivations".

Even the final Satanic coffee clatch is played like brunch

at the Waldorf: "Hail, Satan," they lift their goblets and

chant with all the conviction of conventioners toasting

sprockets and sales figures.

William Friedkin’s The Exorcist

(1973) played it straighter and suffered for it. The stars,

especially Max Von Sydow and Ellen Burstyn, are ridiculous,

trying vainly to get at some of William Peter Blatty’s spiritual

subtext while nearly drowning in green spew. Only Jason

Miller, as the priest who’s lost his faith, and Linda Blair

who, God knows, can find her way around a B-flick, really

shine in this cast. Miller is a slightly more controlled

version of Jeffrey Combs, one of the great horror actors

of the 80s and 90s. Combs can play madness on hold (the

mad scientist in Stuart Gordon’s Re-animator), madness

brewing (the terrified scientist in Gordon’s From

Beyond), and madness de Mille (the totally unhinged

cult expert in Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners).

But it’s all madness and you’re not going to see him standing

next to Robert Zemeckis this March at the Oscars or even

next to David E. Kelly at the Emmys. He’s a creature made

for B-movies and hell, he doesn’t invade Harrison Ford’s

territory, why should Ford invade his?

The Shining (1980), a prestige

picture directed by American expatriate Stanley Kubrick,

further blurred the line between mainstream cinema and exploitation

crud. The Shining’s an odd bird because, while it’s

a prestige picture, the performances are B-movie heaven.

Of course Jack Nicholson, to this day, can run amok through

hamdom like he never left the Roger Corman stables at AIP,

but in this movie he doesn’t even try to contain himself.

And this after prostrating himself before Oscar

several

times during the 70s. He’s all over the place and the critics

savaged him while horror and exploitation fans reclaimed

an old idol. several

times during the 70s. He’s all over the place and the critics

savaged him while horror and exploitation fans reclaimed

an old idol.

The real star of The

Shining however, is Shelley Duvall with her stringy

hair, pop eyes and horse teeth. Why she hasn’t found a permanent

and lucrative home in horror films is beyond me. Maybe it’s

because Robert Altman and other arty directors keep telling

her she’s a star. Let her go hang out with Stuart Gordon.

She’ll have fun. She and Jeffrey Combs can chase each other

around the laboratory with iridescent zombie elixir.

iii.

gandhi and the aliens

After

The Shining, the real trouble started. Perfectly

serviceable horror and sci-fi movies were ruined by "layered"

performances. Great, juicy crap like Species, Mimic,

Wolf (featuring a sadly restrained Nicholson and

a ludicrous Michelle Pfeiffer), The Sixth Sense,

The Haunting of Hill House and What Lies Beneath

(more ludicrous Pfeiffer) were totaled by good acting.

What are Ben Kingsley, Forest Whitaker, Marg Helgenberger

and Alfred Molina doing in Species, a potentially

rip-roaring, sexy alien movie sunk by star power. What’s

Mira Sorvino doing in Mimic? What are Lili Taylor

(really overthinking sexual ambiguity) and Liam Neeson (really

underestimating his  cache)

doing in The Haunting of Hill House? What’s Harrison

Ford doing….well, what is Harrison Ford doing? These films

cry out for Combs, Bruce Campbell, Brad Dourif, Harry Dean

Stanton, Shelley Duvall, Michael Madsen (who is in Species

and tries hard to salvage it), Billy Zane, Jeff Fahey, Geoffrey

Lewis and other ding dongs whose specialty is going from

limp to BINGO! in a blink. cache)

doing in The Haunting of Hill House? What’s Harrison

Ford doing….well, what is Harrison Ford doing? These films

cry out for Combs, Bruce Campbell, Brad Dourif, Harry Dean

Stanton, Shelley Duvall, Michael Madsen (who is in Species

and tries hard to salvage it), Billy Zane, Jeff Fahey, Geoffrey

Lewis and other ding dongs whose specialty is going from

limp to BINGO! in a blink.

iv.

you’re not the man i married

When I was a kid I watched the Saturday night Creature Feature

religiously. I saw a million movies that scared the

hell out of me back then, but the one I remember most fondly

is I Married a Monster from Outer Space (Gene Fowler,

1958). In it, Tom Tryon (now Thomas Tryon and author of

the spooky bestseller, The Other) plays Gloria Talbot’s

brand new husband. On their wedding night, Tom is possessed

by an alien monster that makes him act indifferently toward

his new bride. In fact, he skulks through the house like

a determined ghost while Gloria thinks she may have done

something wrong. After all, this is her first marriage,

maybe she missed something in the instruction manual. This

isn’t the man I married just a few hours ago, she thinks

to herself. But hey, no one said marriage was a walk in

the park, maybe this is just the way it is once the bloom’s

off the rose. Tom Tryon is terrifying in this film just

by being boring and blank and dissociated. In my kid mind,

he was the greatest horror actor I’d ever seen.

Years later, I saw Tryon in Otto

Preminger’s big budget snooze The Cardinal (1963)

and in Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun (1971)

and damned if he wasn’t just as terrifying. Hell, he was

the same character – boring, blank, dissociated. Trouble

was, the film had changed up on him, apparently without

him noticing.

In the three or four moments in

my life when I’ve viewed people in extremis, people barely

hanging onto sanity or who’ve actually become raving things,

they’ve behaved far more like the characters in Deathdream

and Deranged and I Married a Monster from Outer

Space than the A-list actors who inhabit Robert Redford’s

Ordinary People or that New Age fraud, The Sixth

Sense. In fact, for most of the the late 60s my family

was held fast in the thrall of suburban malaise, alcoholism,

the war, adultery, tranquilizers and mental illness. They

became, in essence, unfamiliar with their roles, method

actors untethered from their stock leads. My Dad became

Tom Tryon and my Mom behaved very much like Andy’s mother

in Deathdream. My God, what performances..

(Note:

This column is named for a misunderstanding. While looking

up the film credits for the British director Charles Crichton,

I came upon this entry: Things to Come, Elephant

Boy (1936). For just a moment I imagined what this great

lost picture might look like and then I realized Crichton

had worked on two films that year, Things to Come

and, later, Elephant Boy. Still, I’d like to write

a script someday for this optimistic, wistful and brazenly

exotic science fiction film, starring Sabu and Maria Montez.)

-- Charles Lieurance, October 2000

|