|

This

essay on the aesthetics of ufology grew out of an invitation

by M. A. Greenstein to write a piece for WorldArt magazine on

the subject, specifically – on the relationship between ufology

and the grotesque. Since this aspect of ufology was not my

primary focus, I proposed, instead, a discussion between M.A.

and myself to more fully address her interests. We met twice

and recorded our conversations. After the first audiocassette

was sent to World Art for transcription, the magazine decided

to cut the length of the feature so we never sent the second

recording. Sections of our first conversation were excerpted

and strung together with no editorial input on my part. Even

worse, M.A.’s voice was deleted completely from the final piece,

which resulted in a text that came off as a series of disconnected

proclamations by me on the subject. I was, obviously, not pleased

with this editorial decision. In this new version of the text,

I have combined elements from both discussions. Unfortunately,

the first audiocassette was never returned to us so I was limited

to World Art’s published version of the text as my source. Because

of this, I was forced to emulate World Art’s approach and excise

M.A.’s contribution to the discussion for continuity’s sake.

MK

On

the Aesthetics of Ufology

(excerpted from an interview with M.A. Greenstein)

1997

by Mike Kelley

Ufology

has long interested me as a cultural phenomenon. It has evolved

in many ways since its beginnings in the late Nineteen-Forties

(with the sightings of mysterious air-born lights, the so-called

“Foo fighters,” by Allied bombers over Europe during World War

Two), yet has remained consistent in some regards. I’m particularly

drawn to the stream of ufology where there is an almost utopian

fixation with the hi-tech image of the flying saucer, but this

is paired with an alien being of monstrous form, or other abject

elements. One of the most consistent features of ufology is

this meeting of hi-tech fetishism and symbolic body loathing.

This aspect of it differentiates the concerns of ufology from

a more general cultural fascination with robotics. In most modern

art histories, the aesthetics of technical perfection and those

that relate to images of the deformed body have been set in

counter-opposition. However, in ufology these two aesthetics

are set side by side in a less clear relationship.

Ufology

pictures an aesthetic collision between a housing structure,

the UFO, and an alien element that inhabits this house, in an

uncommon aesthetic mixture of the abject and the technological.

In the Nineteen-Forties, the Wartime framework of the original

UFO sightings rendered the technological aspects of the UFO,

itself, frightening. UFOs were feared as possible examples

of unknown enemy military technology. This concern has faded

over time and the technological aspects of the UFO have taken

on a different symbolic meaning. The clean, orderly, and machinic

nature of the UFO now acts as a foil for the menacing, unformed,

beings that it contains. It is only this, essentially dramatic,

pairing that I would say constitutes the “grotesque” in relation

to ufology. My use of the word grotesque here is meant

to point out the incongruous, and what could at this point be

meaningless, nature of this combination, and is in this sense

a somewhat old-fashioned usage of the term, which was once used

to refer to fantastic decorative motifs. The word, in common

parlance, does not have such playful overtones any more. Nevertheless,

it strikes me as an inappropriate word to apply in ufological

discourse. At present, any discussion of ufology would have

to be understood as one addressing a negative aesthetic. Despite

the fact that the symbolic meaning of its technological component

is unclear at this time, the mythologies of contemporary ufology

are ones of fear and horror. UFO abduction narratives often

describe disturbing intrusionary practices performed upon the

human body. Thus, it seems more proper that ufology be addressed

through contemporary discourses attendant to the abject, and

not the grotesque.

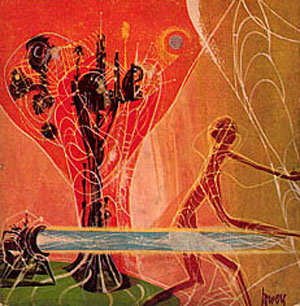

Painting

by Richard Powers; cover of Above

and Beyond by A.E. Van Vogt

Very

few people now hold views similar to those involved in the “space

brother” phenomenon of the Nineteen-Fifties. This group of

UFO devotees drew a comparison between advanced technology and

morals. The assumption was, if aliens have superior machinery

they must, likewise, be more socially advanced. This empathic

notion of the alien was stressed by the fact that they also

looked like us. The film The Day the Earth Stood Still

(1951), which depicts a noble alien who comes to Earth to

save us from our own destructive proclivities, exemplifies this

view of the morally advanced alien and its technology. More

often, however, Hollywood alien invasion films of that period

depict the alien being as evil and totally other, like

the one-eyed blob monster that inhabits the flying saucer in

the film Atomic Submarine (1959). The contrast

between the primordial appearance of such a being and the ultra-sophisticated

device it pilots appeals to me. It prompts the question of just

why there should be such overt design inconsistency between

the form of the being and its craft? The two are so unlike

that they are impossible to reconcile. Its as if I were asked

to believe that the pea soup, or refried beans, that inhabit

a tin can designed that housing for itself, and that this shell

somehow represents its “psychology.” On the symbolic level,

the two forms simply can not have similar meaning.

The

pleasure provoked by this incongruity evokes Georges Bataille’s

aesthetics of heterogeneity. Bataille described the similarity

he felt between such abject excremental forms as sperm and shit,

and the “sacred, divine, or marvelous,” as a byproduct of their

shared heterogeneous status as “foreign bodies” relative to

our assimilating and homogenous culture. They are both, in

a sense, equally taboo. He gives as an example the image of

“a half-decomposed cadaver fleeing through the night in a luminous

shroud”[1]

as one that characterizes this unity. The image of the abject

blob-like alien is part of a long history of images of foul

heavenly masses, sometimes called “star jelly” or “pwdre ser.”

In literary sources and scientific journals spanning the Sixteenth

to the early Twentieth Century one may find descriptions of

“gelatinous meteors” – falling stars that, when located, reveal

themselves as lumps of stinking, white, goo. The evocation of

sperm in such accounts is so obvious that such finds were sometimes

described as “star shoot.”[2] So, a mythic relationship between

the sky and the abject has quite a long history. This conflation

of the heavenly with the abject body recalls Bataille’s example

of the risen Christ, which simultaneously represents rotting

corpse and ascendant being. But, unlike his example, which the

social institution of religion has appropriated into culture

as a divine image, the abject qualities associated with similar

imagery in ufology have maintained their terrifying heterogeneous

nature. Ufology always invokes this connection between the heavenly

and the abject and, so far, this has not been codified to the

point where it could be considered a contemporary religion.

In

Being and Nothingness, Jean-Paul Sartre conducts an analysis

of the “slimy,” attempting to explain why such a quality is

so repugnant. The fact that slime is base, or dirty, is not

the issue. That which is slimy is terrifying, primarily, in

that it provokes an ontological crisis because it clings;

it threatens one’s sense of autonomy, and this is imbued with

an uncanny quality. Sartre writes, “. . .the original bond

between the slimy and myself is that I form the project of being

the foundation of its being, inasmuch as it is me ideally.

From the start then it appears as a possible “myself” to be

established; from the start it has a psychic quality. This

definitely does not mean that I endow it with a soul in the

manner of primitive animism, nor with metaphysical virtues,

but simply that even its materiality is revealed to me as having

a psychic meaning . . .”.[3] Slime’s ambiguous qualities are

accentuated by the fact that its “fluidity exists in slow motion”[4];

it makes a spectacle of its instability. Unlike water, which

instantly absorbs into itself, slime does so slowly giving one

the false impression that it is a substance that can be possessed.

Slime is, therefor, read as a deceitful material. Its in-between-ness,

its boundary-threatening attributes, provokes a base and horrible

sublime experience.

Light,

like water, is generally understood as a kind of transcendental

formless because its undifferentiated qualities are both unitary

and actively kinetic, unlike slime’s earthy weightiness. That

is why it has found such favor in religious imagery in the form

of the halo, and why fixed heavenly bodies, despite their ambiguous

nature and qualities, are not fear inducing. In “documentary”

photographs of UFOs this elevated status is threatened and light

is imbued with negative and terrifying connotations. For, despite

eyewitness accounts that describe “flying saucers” as tangible

technical apparatuses, they rarely have been photographed as

such. Of the innumerable photographs purporting to document

flying saucers collected by the government agency Project Blue

Book[5],

very few reveal any recognizable form. Often, these photos

only show spots of light floating in the sky.[6]

It is not the fact that these photographs image what could be

potentially dangerous technologies in the service of unknown

beings that makes them terrifying, it is their impenetrable

quality that does so. These photographs “picture” that which

cannot be seen - cannot be known. They do so by employing the

sign of the formless – the blob.

Relative

to the image of the alien being, the “unformed” alien is mostly

a product of the Nineteen-Fifties and Sixties. Many Hollywood

films of those eras, and even a few eyewitness accounts, feature

such beings. John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) (a remake

of the Howard Hawks production from 1951) is one of the few

films after that time to seriously address such a conception.

The film’s shape-shifting alien almost seems like an excuse

to show off the wizardry of the special effects crew. The alien

can adopt any form, and the film’s most chilling moments come

when the being is caught in a transitional phase, between fixed

forms. These “slimy” depictions strike me as overtly psychosexual

in nature. The fact that alien invasion films no longer function

as allegories of Cold War political conflicts, throws the symbolic

meaning of the alien into the realm of, interiorized, psychological

conflicts. The moments when the being is discovered in transition

are definitely “primal scenes” within the film. Watching them,

you feel like the child who has stumbled upon mom and dad in

the act of fucking. You understand this is something you’re

not supposed to see. You don’t know exactly what it is

you have seen, but you know it’s something horrible - the merging

of two distinct bodies into one.

By

the Seventies, the dominant alien type is the childlike “gray”

alien as depicted in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters

of the Third Kind (1977). However, abject slimy materials

are still an important element in ufological depictions. The

current literature of alien abduction is rife with abductee

recollections - of immersion in pools of goo by their captors,

of waking to find themselves stained with inexplicable sticky

spots after alien visitations and probings. Less often, the

interior conditions of the alien crafts are described as abject,

as being dirty or foul smelling. This condition is accentuated

in the film Fire in the Sky (1993). The horrific

“in-betweenness” of the slimy in regards to the form of the

alien has been replaced in contemporary ufology with a psychic

in-betweenness – reality becomes liquid as abductees come to

realize that their memories are perhaps only screen memories

implanted by their alien captors. The image of the alien itself

is truly unknowable for it is possible that even that memory

is an implanted fiction. The film Communion (1989) plays

up this aspect of unsure psychic reality by intercutting filmic

“reality” with hallucination scenes so that it is unclear what

the “real” is. The visage of the alien being is presented as

façade - a mask. Reality is indistinguishable from hallucination.

Few

films explore this territory; more often there is a clearly

demarcated division between “our” space and the space of the

alien intruder. Several films of the Nineteen Sixties do explore

this liquidity of space, if only in their “psychedelic” art

direction that pictures biomorphic worlds that themselves teeter

on abstraction. Angry Red Planet (1959) offers an extremely

unusual depiction of the planet Mars, especially given the date

of the film. The scenes on the planet’s surface have been effected

so that they are unnaturally colored and resemble popular psychedelic

graphics of the later Sixties. The visual effects produce a

space that is gooey and indeterminant, and the planet Mars itself,

personified in the form of a giant crawling amoebic organism,

threatens to engulf the space explorers. Barbarella

(1968) is a much more tongue in cheek depiction of psychedelic

space that obvious riffs on contemporary drug culture style.

The evil alien city in the film sits atop the seething “Matmos,”

a shapeless id-organism. This evil manifests itself, humorously,

through sexual perversion in the S&M persona of the city’s

she-witch ruler. The film’s conception of the otherworldly

is dominated by a biomorphic design sense. Interestingly, a

similar ‘alien’ design sense is utilized in the film Fantastic

Voyage (1966) to render the interior space of the human

body – which is revealed as resembling the garish insides of

a lava lamp.

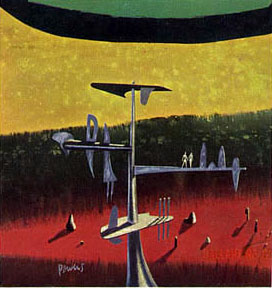

These

visual examples of organic space as depicted in Hollywood films

are reminiscent of the graphic work of Richard Powers, one of

the most active science fiction illustrators of the Fifties

and Sixties[7]. Powers is, by far,

my favorite science fiction illustrator. By the early Nineteen

Fifties, he had broken with the tradition of hi-tech science

fiction illustration, popular since the Thirties, in favor of

a kind of surrealist style. He was alone in this regard. Powers’

illustrations betray the influence of the biomorphic Surrealist

painters Yves Tanguy and Roberto Matta and are extremely abstract.

Figure, environment, machine - are all rendered in a similarly

organic manner so that they interpenetrate each other is a psychedelic

miasma. Powers seems responsible for taking the forms discredited

in the America painting scene by the rise of Greenbergian formalism

- the biomorphic forms of late Surrealist abstraction, and transferring

them to the world of mass culture. It strikes me as obvious

that the success of Powers’ book cover illustrations in the

Fifties paved the way for the explosion of later popular psychedelic

art in the Sixties.

paintings

by Richard Powers

The

rise of the acid-tinged neo-Surrealist pop culture of the Sixties

radically changed the popular notion of the abject; the ‘natural’

was redefined. This is exemplified by the political meaning

of the ‘dirty hippie.’ If you were a hippie, this was understood

as a ‘natural’ condition, if you were not a hippie, this condition

was abject. The popular symbolic representations of disorder,

predicated on images of dirt and defilement, are thrown into

question. This perhaps explains why I so love blob monsters

for, feeling “alienated” myself as a child, I empathized with

them rather than being disgusted by them. Also, since many

blob monsters’ “horrific” nature stems from their thinly veiled

genital appearance, it is only a short step to, as a viewer,

strip this veil away to embrace them as overtly erotic images.

To not do so would be to buy into the repressive sexual attitudes

of those that would depict the genitals as monstrous and alien.

This, perhaps, explains the death of the amoebic aliens of the

films of the Fifties and Sixties and their replacement with

the childlike gray alien of today. The infantile, pre-sexually

conscious, mindset that the “genital” blob alien is directed

toward, has been replaced by one that is sexually conscious

but is fearful of sexual victimization. If these early blob

aliens were “uncanny” in the Freudian sense, that is - they

were genital stand-ins representing castration anxieties (and

this is perhaps confirmed by the number of body part monsters

found in films from this period: the crawling eyes, hands, brains,

etc.), they have been replaced by more overt symbolic representations

of images of child abuse.

As

I pointed out earlier, aliens currently are most often depicted

as childlike beings – small, frail, with oversized heads and

large eyes – almost the cliché Margaret Keane[8]

illustration of the soulful big-eyed waif. But these aliens

are not like our children - they are genderless and asexual

(though they conform in this regard to the stereotypical image

of childhood innocence). They also have no insides and outsides;

because the grays don’t have any orifices we might construe

that they are one pure material - whole. In that sense, the

alien itself could be seen as analogous to Jung’s symbolic interpretation

of the egg-like form of the UFO. He read the UFO phenomenon

as a “collective vision” reflecting a cultural striving for

wholeness and order, represented by the mandala-like shape of

the space ships - a symbolic compensation for the “spit-mindedness

of our age”[9] in the wake of the horrors of World

War Two. Interestingly, Jung explained the societal interpretation

of the UFO as a technological construction as a naturalizing

device, a way to escape the currently out-of-fashion “odiousness

of a mythological personification.”[10]

This aspect of ufology has not changed; the hi-tech image of

the UFO is the same now as it was in the Forties. But the activities

performed inside these ships (primarily beginning with the famed

“abduction” of Betty and Barney Hill in 1961[11])

are quite unlike those depicted in the films of the Fifties.[12]

If the plots in these films reflect the “us vs. them” mentality

of the Cold War period, the new alien abduction scenarios reflect

the battleground of the American family itself. (Though the

recent popularity of the Fifties-style invasion film Independence

Day (1996) signals a possible nostalgic resurgence

of this genre. In this nationalistic fantasy, the unified defense

of the world against alien invasion results in the President

of the United States becoming the President of the World.)

The unchanging image of the UFO strikes me as something of a

conundrum; I would have expected that the technological symbolism

of the UFO would have changed in accordance with shifts in social

symbolism, but this does not seem to be the case. Jung’s reading

of the technological aspects of the UFO as a sign of order remains

firm.

The

scenarios described in UFO abduction accounts are remarkably

similar to the “recovered memories” found in the pop-psychology

literature associated with repressed memory syndrome. This

form of therapy takes as a given the explanation that most adult

emotional problems are the byproducts of, repressed into forgotten,

childhood sexual abuse.[13]

But in ufology the roles are reversed - the childlike aliens

are the abusers of adults. Alien abduction scenarios often detail

painful medical procedures centering on the probing of the body’s

orifices – that which the alien lacks. The abductees are powerless

victims suffering at the hands of emotionless diminuative figures.

Obviously, the similarity of the scenarios found both in “recovered”

memories of childhood abuse and alien abduction accounts points

toward a cultural crisis regarding notions of childhood, sexuality,

and power. Even figures within the world of ufology itself now

say that recovered memories of alien abduction are perhaps only

symbolic, though they also believe that this aspect of the abduction

“phenomenon” is promoted by, and in the service of, the aliens.

Jacques Vallee[14]

writes, “We are compelled to conclude that many abductions are

either complete fantasies drawn from the collective unconscious

(perhaps under the stimulus of an actual UFO encounter acting

as a trigger) or that the actual beings are staging simulated

operations, very much in the manner of a theatrical play or

movie, in order to release into our culture certain images that

will influence us toward a goal we are incapable of perceiving.”

[15]

If

the UFO phenomenon reflects, as Jung puts it, “the split-mindedness

of our age,” it could perhaps be understood to parallel (though

on an unconscious level) the “schizo-cultural” aspirations of

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, whose notion of the “body

without organs” could be applied to the uniform materiality

of the orifice-less alien. Though they, surely, would not empathize

with the pathological reading applied to this current wave of

hallucination. Delueze and Guttarri’s image of the body without

organs is a reaction against the mechanization of the body induced

by conventionalized usage of the organs of sense. As they put

it, “Is it really so sad and dangerous to be fed up seeing with

your eyes, breathing with your lungs, swallowing with your mouth,

talking with your tongue, thinking with your brain, having an

anus and larynx, head and legs? Why not walk on your head,

sing with your sinuses, see through your skin, breathe with

your belly . . .”[16]

Well, yes it is sad if these experiences are simply reducible

to symptoms associated with a group hallucination reflecting

a culturally regressive desire to hold on to outmoded idealized

notions of childhood purity.

At

this point I want to make a U-turn and go back to my previously

stated interest in the blob alien, and my contention that this

could be viewed as an “erotic” image – a fanciful depiction

of, rather than a fearfully sublimated image of, the genitals.

For this to be true, the appeal of the image could not be simply

limited to a perverse reading – that the blob alien is a “dirty”

image that represents a conflation of sexual notions with ones

of defilement. The latter idea would probably be in line with

the original intentions behind the design of such creatures,

but I would like to argue that we are not limited to such a

reading. Now, Sartre’s analysis of the slimy most definitely

addresses the sexually horrific overtones of such substances,

whose clinging qualities he designates as feminine. The female

genitals, and in fact all holes, provoke in him the same fear

of being swallowed up. The conclusion would be that he must

find the sexual act of penetration to be exceedingly horrific.

He especially disdains the “sickly sweet, feminine” and states

categorically that “A sugary sliminess is the ideal of the slimy.”[17] Even so, Sartre

seems to be saying that there is really no hierarchy of sliminess

– sticking ones hand into a pot of honey provokes the same amount

of revulsion as sticking it into a pot of gooey pus. This doesn’t

ring true to me.

The

anthropologist Mary Douglas makes a point somewhat similar to

Sartre’s, in that she points out that filthiness is not a quality

in itself but is a byproduct of a boundary disruption. However,

notions of boundary operate here on several levels. She states,

“Matter issuing from them [the orifices of the body] is marginal

stuff of the most obvious kind. Spittle, blood, milk, urine,

faeces or tears by simply issuing forth have traversed the boundary

of the body.”[18] The problematic

nature of these materials is not so much their phenomenological

qualities (as Sartre would say of the slimy) but that they are

confusing materials, being both part of you and separate from

you. This is similar to Sartre's slime, that provokes an ontological

crisis in its clinging insistence that it is part of you when

it obviously is not. But following on her statement regarding

materials issued by the body, Douglas makes a second point,

“The mistake is to treat bodily margins in isolation from all

other margins.”[19] This notion of boundary is less specifically ontological

and more one of definition and framework – abject qualities

are defined by context. A simple example would be - dirt in

the house is bad, dirt in the garden is good. This notion of

boundary is less all-encompassing than Sartre’s phenomenological

approach and allows for argument about proper usage and definition

of boundaries.

Now,

relative to Douglas’ list of abject bodily materials, it seems

obvious to me that most would agree that some of these materials

are more abject than others are. Very few people would truly

find tears abject at all, and only the most squeamish would

find mother’s milk abject – in any context. I found myself

thinking about this relative abject-ness in relation to pornographic

depictions, specifically the image of male ejaculation, the

so-called “money shot,” and especially the photographic image

of the face with sperm upon it. This image has become a mainstay

of pornographic iconography since the success of the first pornographic

feature film, Deep Throat (1972). My interest

in this image grew out of the question of whether it was possible

to have a sexualized depiction of a blob that was not an image

of defilement. And I would have to answer that yes, I do think

this is possible. Is a photograph of a puddle of sperm, by

itself, abject? Is it necessarily an image of defilement?

Some would find it so, some wouldn’t. Only the most sexually

conservative people, who feel that intercourse is only to be

performed in the production of children, would have such a mechanistic

view of sex as to argue that any visible trace of sperm would

constitute a transgression. Obviously, for many others, the

experience of the gooey-ness of sperm is tactilely pleasurable,

is part of normal sexual activity, and has no negative overtones

whatsoever.

The

money shot has been roundly criticized as an act of defilement

of the female countenance, but is it truly so?[20] Its presence in pornographic films is easy to

explain – it proves that male orgasm has occurred, and this

is located in proximity with the traditional site of female

displays of ecstasy: the face. Male and female orgasm is presented,

in one frame, as simultaneously visible. Pornographic films

are participatory; they are designed specifically for men to

masturbate to. The male viewer’s fantasy investment in them

is predicated on their “documentary” nature – that they are

“real” displays of pleasure, which is proven by the visible

act of ejaculation. The viewer’s pact with a pornographic film

is predicated on this shared experience with the surrogate version

of himself acting in it.

An

amusing result of the rise of the money shot in pornography

is the result it has had on the reading of earlier “spiritualist”

photography, specifically the genre of photograph that depicts

the medium exuding “ectoplasm,” a white substance that it said

to flow from the orifices of a medium in a trance. A photo

of the medium Mary M., taken in Winnipeg in 1929, shows the

cotton-like material caught in the female medium’s hair, and

pouring from her ears, nose, and down her chin onto her breast.

Her eyes are rolled up in the ecstatic pose familiar from pornographic

photos from the same period, a gesture that seem derived from

ecstatic countenances found in Christian religious imagery.[21]

Another photograph depicts the material running from between

the medium’s legs into a heap on her feet.[22]

The sexual connotations of such imagery is so obvious that it

could not be produced now without it looking like it was designed

specifically to reference the money shot, a pornographic trope

that was not even present in pornographic photography of the

Twenties. The fact that these photographs strike us as funny

reveals the fact that such overt sexual connotations are incompatable

with spiritualist imagery, that the “sexualizing” of an image

is a form of defilement. On the other hand, our present problem

with ectoplasm photographs could simply be that the displays

of ecstasy depicted in them strike us as too mannered to be

believable at this time – that they are not convincingly

erotic. If it weren’t for that fact, perhaps such imagery

could maintain its transcendental value despite its sexual overtones.

I prefer this second interpretation; if it is true, then my

desire for erotic depictions of blob monsters is a possibility.

UFO

photography has taken the place of early Twentieth Century spiritualist

photography as the dominant mode of supernatural imagery. The

fact that many UFO photographs look as obviously faked as ectoplasm

photographs (a fact that can be forgiven in spiritualist images

since photography was still invested with truth value in the

early Twentieth Century) doesn’t really matter. These are images

of faith more than they are “documentary” photographs, and in

that sense UFO photographs are a true folk art form representing

what are, at this point, traditional and commonly held beliefs.

Still, as I stated earlier, this belief system has not yet been

appropriated into mainstream culture in a “homogenized” way.

It does not yet function analogously to a true religion. Despite

the commonplace nature of the UFO mythology at this time, it

is still held in disdain, still considered a “crackpot” belief

system. As such, it maintains its “heterogeneous” cultural

position and its terrifying overtones.

|